Latest news, and continuing efforts to make sense of things, starting with:

1. Sax QT (Lorraine) 2022. I did buy a copy of this four-CD box set, and have been gradually working my way through it. I can't pretend that it leaves me fully able to answer any of my own questions regarding the true nature of the Lorraine system, but the music is extraordinary - amazing, sublime even.

The overall level of design and finish on the actual box set is very high, although the outer box itself is of the type that will probably "separate" a bit at the top hinge (so to speak) - there's nothing much to be done about that. The front cover itself is of course visible on the Bandcamp page, this being the design for the front of the outer box, of stiff white cardboard; inside we have a 40-page booklet and the four CDs themselves, each individually housed in its own cardboard sleeve with its own cover, and full recording credits on the rear.

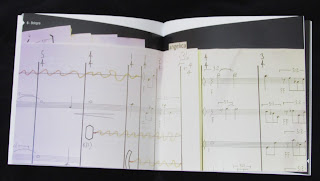

The discs themselves are presented after the fashion of the colour-scheme on the front of the booklet, which includes an essay by Mario Gamba (in Italian, and also in a slightly eccentric English translation), many full-colour photos from the various shows, detailed credits and a close-up detail from the score for Comp. 437 (Bologna): *

Really, given the costs involved in putting this sort of thing out in the first place, a friendly experiencer would have to be very picky indeed to find any fault with this purchase**. The presentation and finish of the discs and their individual sleeves compares very favourably with other such sets (especially with this one), and the whole thing rather left me wondering how the label expects to make any profit out of this; then again, it's not exactly cheap (and besides, when it comes to business... what would I know about that?). Full marks for the packaging, anyway. I am, indeed, a very satisfied purchaser.

As for the actual content - as always in such cases, my responses to the music have varied according to how much attention I was able to give proceedings while it was playing. In the case of the Vilnius disc - Comp. 436 - I listened pretty closely and did very little else while it was on, and the music left me almost speechless with admiration. The sheer quality of the playing is hardly a surprise; it would be a surprise if there were anything to complain about on that front. But of course in these cases, none of the players were "side(wo)men" exactly: with all three of B's collaborators for each concert being very highly trained in his music, and extremely experienced at interpreting and playing it, what we are dealing with is not so much a saxophone quartet as a tight-knit cluster of soloists - and the attentive listener is continually reminded of that, from one bright moment to the next. I can't say that I was equally conscientious about hearing the other three discs - yet! - but I have played all four, and none of them disappoint. Electronics, though present, are used rather more sparingly than in a DCWM context; primacy is definitely given to the aerophones, and to the "sonic winds of breath" which B. has talked about in the context of this new system. I still can't claim to have emerged with a very clear sense of what makes the new music different, but as I observed earlier this month, it is obviously quite different for the musicians while they are playing it.

***

2. In my last post, I began looking at GTM from a theoretical point of view, and listed all the opus numbers which I can personally say for sure belong to this extensive system***. Along the way, a few vexed questions arose - when do they not, in doing this sort of work? - regarding details which vary from one official release to another. Something which I thought I might be able to clear up does not actually concern GTM at all: is Comp. 307 a solo series, or a single work? The former seemed far more likely, and when I dug out the digital files for the Guelph release, I was first looking to rule out GTM; having quickly done so, I discovered that track four on that release - listed as "Composition 307 / Language Improvisation" - is a feature for female vocalist, which (I thought... wrongly) should be easy enough to track down. The singer's first entries on this piece ("Here's looking at you, kid/ Yes sir, right this way, please") were quite familiar to me, and I was sure that I had heard them most recently sung by Anne Rhodes, as tertiary material worked into one of the SGTM pieces#. The reference to giving directions, or guiding somebody, made me wonder if it was an excerpt from Comp. 173, which would after all make some sense (at least two of the digits are correct, albeit not in the right order: 173 > 307? not unthinkable); but I later listened to that work all the way through, and drew a complete blank##. From there, I turned towards the various parts of the Trillium cycle, which rather represents the "here be dragons" zone of the larger map, as far as this opera-resistant listener is concerned; as I have said many times before, I struggle with this stuff, although I have lately felt closer to being ready for it, and besides: I am sure that if I could see some of it performed I would engage with it that much more readily.

Anyway, cutting to the chase here: I did try to locate the relevant passages in both Trillium J and Trillium E, but was unable to do so, and for the time being, I must admit defeat. Trillium E, again, seemed tantalisingly plausible: it is designated as Comp. 237 in the numbering system, which would quite easily allow for a typographical slip in preparing the Guelph recording for release... Trillium J bears the opus number 380, which is still not completely unlikely... but I did scoot through both of these works in search of the text in question and didn't find it, although of course I have not listened to either of them all the way through yet. (I will assume that wherever this passage originally occurs, it is sung by (coloratura) soprano, if Rhodes has it in her repertoire.)

Whatever track four on the Guelph release is, though, I am pretty sure it's not "Composition 307". And that's where I have to park that puzzle, for the time being...

***

3. For all my recent fussing over which composition goes in which category, it wasn't until just after my last post that I stopped to think about another piece with a high opus number: Comp. 403, as seen on one of the few "official bootlegs" which are still available for download: 10+1tet (Knoxville) 2016. This being a bootleg, we can consider ourselves lucky to have been given an opus number at all (... although perhaps we might ponder whether its accuracy is less than certain), and the fact that we also have a date, a venue and full personnel is really all that we might reasonably expect. Tertiary materials being listed as well..? That is icing on the cake### ... one need not anticipate any notes, and of course we didn't get any. But when I first downloaded this piece and listened to it (whenever that was exactly... some time last year, at any rate), I really didn't wonder about what I was hearing. So it's only now that I have asked myself: what is this music?

The only other pieces I've come across with (semi-reliable) numbers in the 40x range belong to the ZIM system; both of the recordings which have been shared with us from the 2016 Big Ears Festival (in Knoxville, TN) have numbers in the same range, but neither of them is likely to relate to that compositional strategy. When I first saw the listing for Trio (Knoxville) 2016, I just assumed it was DCWM - and perhaps it is; or perhaps it's FRM, or (more likely) one of these eldritch modern hybrids, the true nature of which I still don't understand. But I can't say I gave it much thought - and I can't say I gave any thought at all to the piece which had been played the previous day. Now that I am thinking about it, I am really none the wiser because I just don't know what sort of new musical ideas were being discussed between B. and his select cadre of musicians at that time, beyond those we already know about. The footage from the rehearsals for the performance - included in that same SGTM video already referenced in this post - only show B. explaining how the players should think of 3rd species, accelerator class GTM (... meaning that they were about to start workshopping Comp. 355). There is no indication at all of which system the primary territory belongs to. I did try a bit of online research, which led only to further questions. The website for Tim Feeney - who plays percussion on 403 but was otherwise unknown to me - has a page on which he details a collaboration with his "Tuscaloosa colleagues Holland Hopson, Andrew Raffo Dewar, and the legendary composer and saxophonist Anthony Braxton" - wait, when was this exactly? - which "grew from (B's) spring 2015 residency at the University of Alabama. In early August 2015 the quartet recorded four hours of new music, combining improvisation, fragments of music from older compositions, and a new system of performance logic and graphic notation, ZIM Music"^ ...

They did? This was a thing? What happened to those recordings? (For a famously prolific composer. the maestro manages nevertheless to do a lot of stuff which never gets officially documented - or, in this case, apparently did get documented, but has not seen the light of day. Hands up who knew that Dewar had worked with B. again as late as 2015..?) - The placement of the link to TCF's Bandcamp page for the 10+1tet almost makes it look as if he Feeney is proposing this as an example of the "unique" new work he was just talking about, but no, it's just the one place where recorded evidence is available of his having played with B. at all. It's not that I have any reason to disbelieve him - only, I went looking for possible answers and all I found was more unknown variables, dammit. Could 403 be an (expanded) example of the hybrid work described on Feeney's site? The only blueprints we have for the ZIM system suggest that doubled-up harps constitute an essential ingredient, and that there is never a string bass or any percussion... whilst in Knoxville we have both of the latter - even if Feeney's role here is most definitely not that of a "drummer" - and no harps at all (although we do have two guitarists, so...). Questions, just more questions.

But you know what? I can park this for the time being, as well. I would like to know, but it's not going to keep me awake in the meantime. What's most important about this recording, which features plenty of familiar alumni as well as guest luminaries from the creative scene in the guise of Brandon Seabrook and Nate Wooley, is that it's fresh and new and vital (even if it is eight years old already). Those lucky attendees in Knoxville got to witness something hitherto unheard, and in an era when many genres are busily swallowing their own tails, not everyone can say as much. But we can always trust our man to keep forging ahead, even while he takes time to look backwards; he never stops, and he never will, and don't we just love him for it?

* These pictures aren't great, but they are functional / illustrative, which is all they were really intended to be. I didn't feel like taking any great time over them - !

** Of course, I am very picky indeed, but even I would only offer the observation that perhaps the essay in the liners is not the most penetrating in terms of insight... the writer certainly gives the impression that he is familiar with B's back catalogue - or parts of it - but he may not necessarily be the best placed to say what is or isn't strikingly original about these performances: I mentioned before the label's rather bizarre fixation on how little B. had written for saxophone quartet, as such, and apparently that originated in these liners. Gamba seems blissfully unaware of the existence of B's saxophone quintets, nor does he seem to realise that in plenty of GTM contexts, as many as seven saxes have been deployed...

*** This may be a good time to mention that I'm not 100% sure of Comp. 199, which feels more like an unusually safe educated guess: as far as I know, it only appears on Toronto (Duets) 2007 (with Kyle Brenders), which is still an unchecked entry on my wants list. But all such duo albums from anywhere near that time feature GTM, GTM and more GTM... I felt sure enough to include it.

# I was right, for once; the video which I wrote about last year shows AR dropping this same material into Comp. 265 (disc nine of the NBH008 box), beginning at 11:41 (- that is, 11:41 on the video, not the actual disc).

## Actually, as soon as I started listening to 173 it all came back to me: its libretto does indeed involve people being guided - sort of - but there's hardly anything that (dare I say it) conventional in there. No, this irresistibly crazy work has to be heard to be believed, in case anyone hasn't... Instrumental readings of (parts of) it are available, and I have heard those more recently, hence my forgetting the character of the sung parts until I was reminded.

### All three listed tertiaries are of course GTM pieces - not just 355, which is what we see the group being introduced to in the rehearsal footage from the SGTM video. (On the subject of tertiary materials: the list for Comp. 404 comprises vocal pieces exclusively, and although vocal works are sometimes interpreted by all-instrumental ensembles, in this case I will assume that the tertiaries were picked with Kyoko Kitamura in mind - and may indeed have been chosen by her beforehand. 219 was the second ever SGTM composition;

237 and 380 are, of course - as was noted earlier in this post - Trillium E and J respectively.)

^ All bold and italic text in this quoted material was added by me.